“Early in November, 1887, John Nolan and other half breeds were near the forks of the Red Deer and South Saskatchewan when they came across a bunch of eleven buffalo, one of the bunch being a very large bull. They killed the big bull, two cows and a calf and brought them into Swift Current. J. Grant got the head of the bull and Curry Bros., got the two cows heads and hide of the calf. No doubt afterword the half breeds cleaned out the rest of the bunch for they were never heard of again.

“Hine of Winnipeg mounted the bull’s head and in 1893 it was loaned to the government and was sent to the World Fair at Chicago, where it was much admired…

“The country lying between the South Saskatchewan and the Cypress Hills and Old Wives Creek and the lakes and the Vermillion Hills was famous for Buffalo and even now the old Buffalo trails and wallows are to be seen from Moose Jaw to Medicine Hat.“

from a letter by “Wyoming Bill” to the Fort Macleod Gazette, 1902

Treaty Seven was signed in 1877. Barely ten years later, Canada’s last wild plains bison expired its last breath into the prairie sky.

Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, thought the eradication of North America’s largest land mammal was a very good thing. “I am not at all sorry,” he said to Canada’s House of Commons in faraway Ottawa. “So long as there was a hope that bison would come into the country, there was no means of inducing the Indians to settle down on their reserves.”

The treaties at least assured the Indigenous tribes of the western plains that they would not starve. In exchange for that and other assurances, they settled on the reserves they had chosen and tried to come to terms with a world turned upside down. How could there be no buffalo?

The Ghost Dance movement that originated with tribes who lived in the Great Basin region of the US spread through many of the plains nations. It was a spiritual practice whose adherents hoped would bring back the world they had always known, including the vanished bison. They were desperate in their loss; a world they had never imagined could end, had.

But the bison were gone for good. Settlers were coming to populate the empty plains. The newcomer people replaced the native bison with a newcomer animal: the domestic cow.

MacDonald’s government wanted to build a new nation from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, and to secure its control over that nation before the Americans, who had a head start on settling the west, could appropriate the place for themselves. That was the basis of MacDonald’s National Policy. His government’s problem, however, was that the land was vast and there were people living there already. The decision to negotiate treaties with those native peoples was, from the Dominion of Canada’s point of view, more a pragmatic than a principled one. They needed peace and order, so they had to negotiate.

As soon as the treaties were in place, the Canadian government started cutting other deals to secure its control over the land. First they arranged to build a railroad across the southern edge of the country. Until that was done there was no practical way to fill the place with farmers. So, as an interim measure, the government issued grazing leases of up to 100,000 acres to well-financed eastern Canadian and British investors.

That was another pragmatic decision. For one thing, it pre-empted any move by Americans to settle the lease lands. The new railway could ship beef as a source of revenue to start paying down its debt. And, perhaps most importantly: the government had promises to keep. It needed a supply of meat for thousands of Indigenous people now faced with the prospect of starvation.

The first huge grazing lease went to a well-connected Ontario conservative, Matthew Cochrane. He sold shares in his Cochrane Cattle Company to a few wealthy friends from Montreal and the Eastern Townships, imported some breeding stock from Europe, and arranged for two big shipments of mixed-breed cattle to be trailed north from Montana. The new lease was centred on what is now the town of Cochrane; the home ranch was at the mouth of Bighill Creek.

Cochrane and his investor friends hired a well-respected mountie, James Walker, to run the ranch. Walker was a rigid, letter-of-the-law kind of guy, which had served him well as a policeman. When his bosses told him to do something, he did it. Unfortunately, that obsequiousness didn’t serve him well in his new job.

The investors had put a lot of their money into this new ranching enterprise, and they wanted to see profit sooner rather than later. They told Walker to get those American cattle onto that Canadian grass as quickly as possible. He followed their orders diligently, pushing a herd of 6800 tired cattle hard in order to get them to the Bow River grasslands before winter. They arrived in bad shape just in time for one of the hardest winters on record.

Cattle aren’t bison. When the north wind blows, bison turn their big, hairy heads into the wind and paw away the snow, grazing their way into the storm. Cattle turn their backs to the wind and drift ahead of it. When snow covers the grass, from a domestic cow’s point of view the grass has gone. They don’t crater down to it like bison, elk or horses do.

Bison would have weathered the hard winter of 1881-1882 easily, but they were gone. The newly-imported cattle piled up against fences or in the deep drifted snow of coulees and river breaks. Most died.

The following year, again following orders from eastern bosses who had no idea of the West’s environmental realities, Walker drove another 4300 head of cows north from Montana during a dry, thirsty summer. The same disaster happened all over again that winter.

Of the more than 11,000 domestic cows Walker brought north, by the spring of 1883 only 4,000 survived. Coyotes and eagles had a great spring; there was food galore. It was not a great spring for wealthy white men with high hopes for extracting big profits from the far frontier. They blamed Walker, even though he had simply followed their orders.

Only two decades earlier, there had been hundreds of thousands of bison here. They knew how to live there. So did the people who lived among them. But the future had arrived. Nothing about it was going to be easy, now that the place was full of strangers.

A century and a half later, the human population of Alberta has increased from less than 50,000 at the time of Treaty Seven to almost 5 million today. A gridwork of roads crisscrosses the plains and continues to metastasize into the boreal north. Towns have grown into cities and cities have grown into metropolises. It might seem like the buffalo days have been left forever in the past.

That would be a misconception. The buffalo have returned. Their reappearance in a land that had almost forgotten them might seem as impossible as their original disappearance was to the Niitsitapi who had lived with them so long. Even so, it is well underway. Who knows what might happen next?

I met Wes Olsen in the early 1980s when I was assigned to a bird inventory project at Elk Island National Park, east of Edmonton. I was still with the Canadian Wildlife Service, and Wes was a park warden responsible for the care of the park’s herds of pure-strain wood and plains bison. Tall, moustached and soft-spoken, Wes comes across more like a cowboy than an ecologist, but appearances can be deceiving: he is North America’s leading authority on the ecology and reintroduction of bison.

Wes was responsible for keeping Elk Island’s herds free of disease and for helping keep the population in balance with the available supply of forage. That meant that the herds had to be culled periodically. Rather than kill the surplus animals, though, Wes and his colleagues arranged for them to be transferred to new homes: bison ranches, small display herds in other prairie parks, First Nations reserves and even an ambitious project to restore some of the original Pleistocene megafauna to northern Russia. The Elk Island animals are considered the gold standard for bison recovery because they contain no domestic cattle genes and are kept free of the diseases that domestic cattle brought to North America. Anthrax, brucellosis and tuberculosis have infected other conservation herds, including those in Wood Buffalo and Yellowstone National Park.

When Pierre Trudeau’s federal government established Grasslands National Park in the Frenchman’s River area of southern Saskatchewan in 1981, the park had no bison. Parks Canada imported plains bison from Elk Island in 2005 and, soon after, imported Wes Olsen too. As the herd grew, Wes and his wife Johane Janelle studied the ways in which the big animals changed the prairie and its wildlife fauna. They soon realized that, just as the absence of bison had changed everything, their return also changed everything — for the better.

Bison wallows create small hollows that fill with meltwater each spring and create breeding habitat for frogs and insects. Bison shed their wooly underfur each spring; songbirds use the wool to line their nests. Bison wool not only provides superior insulation for eggs, it also disguises the odour of the nestlings, increasing both hatching rates and nestling survival. Literally hundreds of species of insect and other arthropods are attracted to bison droppings. Some of those insects burrow into the ground, increasing the soil’s porosity and enabling rain to soak in more thoroughly. Others are vital food sources for horned lizards, loggerhead shrikes, sage grouse and other species that were once abundant but are now endangered. In winter, pronghorns, deer and grouse feed in the snow craters that grazing bison carve out of the snowpack.

Wes describes the plains bison as a keystone species — a species whose presence or absence has much more far-reaching effects on their ecosystem than other animals. Beavers are another keystone species. So are we.

In 2022 Wes and Johane released The Ecological Buffalo, unquestionably one of the best books of applied ecology ever published in Canada. It details the many threads of connection linking plains bison and the rest of the prairie ecosystem. The sheer complexity of the relationships Wes and Johane describe is a sobering revelation of what was lost when that last prairie bison fell to a hunter’s bullet a century and a half earlier. But it is also an awe-inspiring revelation of what prairie Canada might again be, if the bison were to return.

And it’s not a question of if, any more. It’s happening.

In 2005, bison returned to Grasslands National Park. From an initial release of 71 young animals from Elk Island, the herd has grown to more than 500. Their trails, wallows, dung and grazing patches again shape that relict prairie ecosystem. They graze among prairie dogs and long-billed curlews. Their odour mingles with that of sage and wild rose. The place is real again.

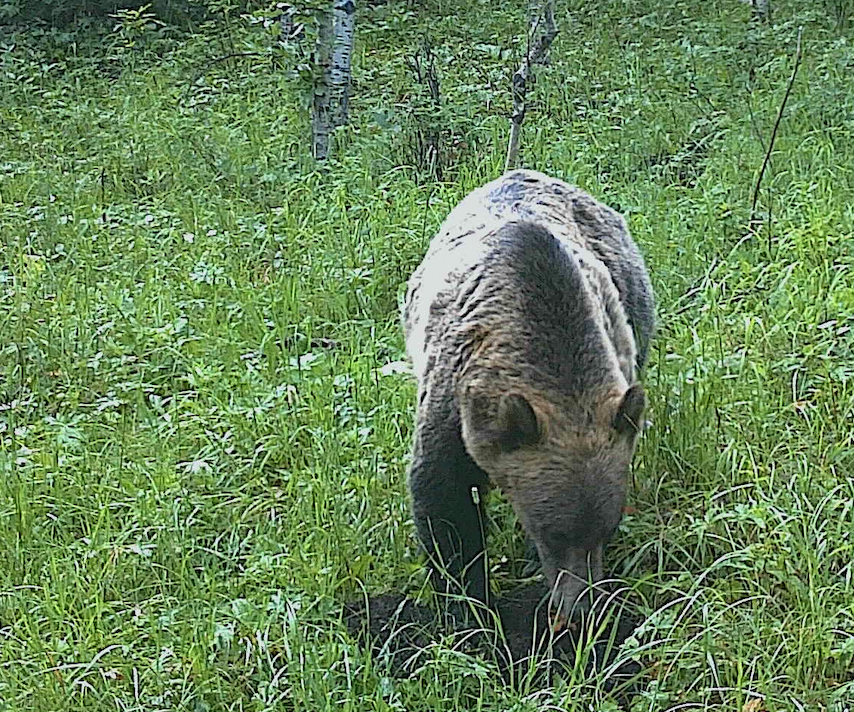

Thirteen years later, another 16 plains bison went from Elk Island to a new home in the wilderness of northern Banff National Park. That herd, which regularly encounters grizzly bears and wolves, has since grown to more than 100. They range widely from alpine meadows through burned-off mountain slopes to the fen meadows along the headwaters of the Panther, Dormer and Red Deer Rivers. The herd may soon outgrow the available range. The need to trim the herd has led to another restoration — that of the age-old hunting traditions of the Iyarhe Nakoda and Siksikaitsitapi. The return of bison to Canada’s first national park — a park whose origin story includes the ejection of those Indigenous people whose homeland it had always been — may help heal more than just the land.

“What would happen if you took the cross away from Christianity?” Kainai elder and teacher Dr. Leroy Little Bear said when I interviewed him in 2017. “The buffalo was one of those things. The belief system, the songs, the stories, the ceremonies are still there, but that buffalo is not seen on a daily basis…The younger generation do not see that buffalo out there, so it’s out of sight, out of mind.”

Little Bear played a pivotal role in drafting the Northern Plains Buffalo Treaty, the first Treaty among Indigenous nations in over 150 years. Initial signatories in the fall of 2014 included the Siksika, Piikanii, Kainai and Tsuu T’ina First Nations as well as Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, Sioux, Salish and Kootenai tribes from south of the 49th parallel. The Stoney Nakoda First Nations signed on a few months later. Other First Nation groups continue to join the treaty each year.

“The Buffalo Treaty is very historic,” says Little Bear. “A treaty among just Indigenous cultures to work together on common issues: conservation, culture, education, environment issues, economics and health research. In the centre of that is the buffalo.”

“Our elders said, we want to restore the buffalo. But it’s a big job. We can’t do it on our own. We need partners.”

Marie-Eve Marchand, a passionate conservationist of Quebec settler stock, is one of those partners. She was a founding member of Bison Belong, an advocacy network formed in 2008 to pressure Parks Canada to follow through on its commitment to bring bison back to Banff National Park and to build social license for the initiative. That work successfully completed, Marchand moved on to provide administrative support and media coordination for the Buffalo Treaty. She worked with both Niitsitapi and their allies from among the newcomer peoples on the Iiníí Initiative, which was meant to rematriate bison in Niitsítpiis-stahkoii — Blackfoot territory.

“We eliminated the beaver and the bison, both keystone species,” she says. “Now we are turning that around.”

“With the return of the buffalo,” Dr. Little Bear adds, “those things that were part of those regularly occurring patterns in nature, the buffalo was part of it. So we’re bringing back those regularities and those regularities are part of what anchor our societies.”

“But there’s a whole lot more. There’s also their larger role in the ecosystem. As a human species, we play a very small role in that ecosystem. And it’s a big job to bring about an eco-balance. So we need help and the buffalo will do that.”

Two years after the initial signing of the Buffalo Treaty, the homecoming of Iiníí became more tangible, with the arrival of 88 plains bison in northern Montana from Elk Island National Park. Their new home was a tribal ranch on the Blackfeet Reservation. They were home, but still behind fences. Then, in 2023, the Blackfeet released 25 bison into their ancestral range on the foothills slopes below Ninaistako. Wild bison were back in the Crown of the Continent.

Tristan Scott of the Flathead Beacon was present to report on the homecoming. Tribal elder Ervin Carlson told him, “To see them out here, it just choked me up. It’s a real good feeling. It finally feels right, after feeling wrong for a long time.”

It finally felt right. But for most of the twentieth century, it was unimaginable. Our only bison story was one of loss. What else might we imagine? We live in a landscape our choices shape, and in a landscape of possibilities our stories create. We have a new story now, a better one. Those landscapes are changing for the better.

If the bison can come home, perhaps we can too. All of us, together, as the Treaty People we are meant to be.