[originally published in 2013, this is extracted from my book Our Place [https://rmbooks.com/products/our-place ].

I’m posting it in light of a newly-published study by Jonathan Farr that documents a 33% reduction in the area of alpine meadows in Banff over less than a quarter of a century. You can read Cathy Ellis’ article about it here: https://www.rmoutlook.com/banff/i-was-blown-away-study-shows-climate-change-dramatically-shrinking-banffs-alpine-meadows-11052721 ]

Wading a cold river in the rain was not how I wanted to start day three of a nine-day wilderness trip in Banff National Park, but there was no alternative. Since my last visit, 35 years earlier, Parks Canada had demolished the bridge across the Panther River and re-christened the fire road as a trail.

When I first hiked the Cascade Trail in 1976 it was a good gravel road all the way from Bankhead, near Lake Minnewanka, to the Red Deer River. Park wardens and horse wranglers regularly drove its 80 km between the town of Banff and the Ya Ha Tinda horse ranch east of the park. They still used the Spray and Brewster fire roads too. Years earlier, in fact, the road sometimes opened for public use; my grandfather used to drive in to fish lakes that are now a two-day hike from the trailhead.

Thirty-five years after my first visit, however, the road was grown in with willows, hairy wildrye and dryas. Mine were the first human footprints this year on what had become a seldom-used single-track trail. Yesterday I had waded Cuthead and Wigmore Creeks several times, growing increasingly nostalgic for culverts, and today—June 26, 2011—I had my first major river to ford.

Icy water tugged hungrily at my knees as I picked a downstream route across a gravelly riffle. I emerged safely, feet aching, into a tangle of rain-dripping willows. Upslope from the willows the vegetation opened into a burned-off pine forest with lush tussocks of rough fescue—Alberta’s provincial grass—and clumps of healthy young aspens.

Sitting on a fallen log to trade wet runners for dry socks and boots, I reflected on how much had changed since my last visit here. That first hike was at the start of my career with Parks Canada; this one was at the end. In the late 1970s I was a Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS) biologist working on the original wildlife inventories of the mountain national parks. A third of a century later I retired as superintendent of Banff, Canada’s oldest, most revered and most controversial national park.

On that first solo foray along this route I saw no rough fescue and no young aspens. Heavy, sustained grazing by the elk that over-populated the park through much of the twentieth century had repeatedly killed young aspen sprouts and suppressed the most palatable grass species. Never having known a Banff that wasn’t defined by grazed-down meadows, aging aspens black with scars as high as an elk could reach, and fire roads extending back into nearly every valley, however, nothing about that trip had seemed unnatural to me. It was the Banff I knew.

Some years later, I helped biologist Geoff Holroyd compile final reports on what our CWS study teams had learned through many months of measuring and counting just about anything that moved anywhere in Banff and Jasper National Parks. The ecological land classification of which our wildlife inventory was part was the most exhaustive study of ecological conditions ever undertaken in the mountain parks. By its conclusion, I had learned that lovely scenery can conceal a lot of ecological problems.

And we hadn’t even begun to think seriously about what climate change might mean to Banff.

The sad state to which the park’s aspen groves, willow thickets and fescue grasslands had deteriorated by the early 1980s was partly the result of too many elk and partly the result of too little fire. The too-many-elk part of the problem resulted from too few predators, especially wolves. They were then only beginning to re-colonize the southern Rockies after having been poisoned and shot out during the 1950s and 1960s. Bears, too, can be important predators on elk calves. Bear studies by Stephen Herrero, David Hamer and Mike Gibeau, however, showed that the park’s many roads and poorly located trails were displacing grizzly and black bears from their most productive habitats and exposing them to increased risk of conflicts with people and collisions with vehicles and trains.

The too-little-fire part of the problem had a lot to do with the determination with which Parks Canada and neighbouring agencies fought back whenever fires flared up after lightning storms or human mishaps. Fire is among the most important agents of ecosystem renewal in western Canada. Lodgepole pine, aspen, rough fescue and countless other species rely on wildfires to put potassium back into the soil, open up the vegetation canopy, knock back competing plants and produce ideal conditions for regeneration. But, by the 1980s, fire had become almost a stranger to the forests and grasslands it had helped sustain for millennia.

The Cascade Trail I was following, in fact, was originally a fire road built so crews could quickly extinguish backcountry blazes.

As I set off up Snow Creek along the former fire road on this June morning I was surrounded with the blackened spars of dead lodgepole pines. Parks Canada’s fire crews had not fought these fires—on the contrary, they had ignited them. Since the late 1980s Banff’s fire specialists have been recognized as international leaders in the science of using prescribed fire to restore ecosystem health.

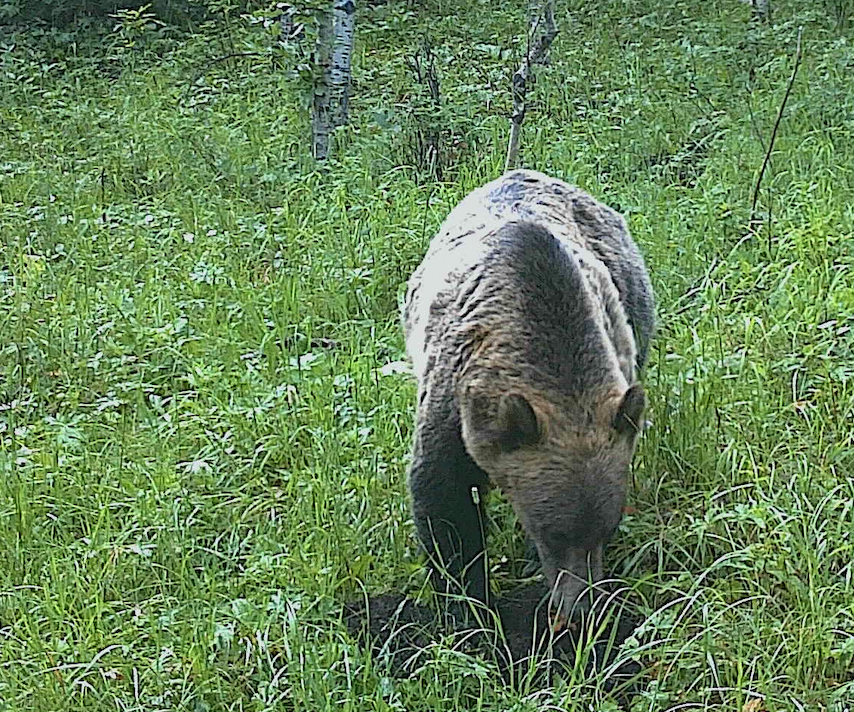

As an ecologist, I was gratified to see the results—a patchwork of hillside grasslands, aspen woodland, patches of unburned pine forest and lush shrubbery where three and a half decades earlier I had hiked through a monotony of pine trees. As a hiker, however, it proved a bit disconcerting. A short way up the trail, I rounded a bend to see a grizzly bear eating sweetvetch roots 60 metres away. A quick glance around confirmed that, should events demand that I climb a tree today, I’d be out of luck. They had all been burned through.

The bear, however, fled the moment he spotted me. I don’t know how many human beings he had seen in his life, but I was almost certainly the first one he met in 2011.

During the first eight days of this wilderness pilgrimage the only sign of humans that I saw was a single horse track. And yet, I knew the park was crowded with people. More than three million visitors flock to Banff each year. There were major special events scheduled for the area near the town of Banff during the time of my hike, and the campgrounds were full. Yet mine were the only tracks amid this mountain beauty. It seemed strange.

A long walk in the lonely wilds is a good opportunity for contemplation. Reflection has a particular edge and poignancy when it comes at the end of one’s career. What, if anything, had Parks Canada gotten right during my working years there? Several days later, when I finally arrived at Lake Louise, I had concluded that we had managed to get a lot of things right.

Banff is in a wilder and more natural state today than back when I first discovered it. Wilder, because fire roads like the Cascade have been closed to motor vehicles and turned back into trails, while at the same time unnecessary facilities and fences were pulled out of front-country valleys to remove obstacles to wildlife movement. More natural, in part, because fire and wolves are back. The ecosystem has responded with fewer elk, more aspens and fescue and greater vegetation diversity. More natural, too, because bears no longer feed in garbage dumps, and in foraging for natural foods across the mountain landscape they are far less likely to die on the Trans-Canada Highway now that it has been fenced and fitted with crossing structures. Grizzlies die unnatural deaths today at less than half the rate they did in the early 1980s.

Clearly, the elements of Banff National Park’s ecosystems that respond to park management decisions such as whether to close or fence roads, ignite prescribed fires, protect wolf dens or open up corridors of secure habitat for sensitive species such as grizzlies, cougars and wolves had all improved. Challenges remain—like too-frequent deaths of bears from collisions with speeding CP Rail trains and the spread of invasive plants and fish—but on the whole, today’s Banff is in better shape than it was when I joined the organization that manages it.

I should have felt good, but I didn’t.

Banff and Canada’s other national parks face bigger challenges than Parks Canada can solve by itself. Global changes, resulting from the thousands of decisions people make daily across the continent, threaten to overwhelm even the best cared-for of park ecosystems.

I was painfully aware that Banff had recently seen the loss of its last caribou—the first large species extirpated since park establishment. I also knew that Alberta glaciers have shrunken more than 25 per cent in the past 35 years – a worrisome omen of impending water challenges. But other changes I saw on my 2011 hike led me to suspect that global environmental change is causing less obvious, but more pervasive, ecological damage throughout the park.

From its earliest days, flower-strewn timberline meadows have been among Banff National Park’s defining elements. Up where forests end and the alpine emerges, generations of artists have been enthralled and hikers inspired by the beauty of timberline. Clumps of subalpine fir with gnarled old larches and whitebark pines frame almost impossibly lush openings full of glacier lilies, windflower, paintbrush and valerian. The first time I broke out into Banff’s timberline country I felt like I had arrived in Middle Earth—it was hard to conceive of so much beauty set against such peaks.

Snow Creek summit was one such place. After 35 years I couldn’t wait to see it again. To my dismay, however, its timberline meadows had almost vanished. Openings once full of greenery and wildflowers were now packed with dense young subalpine fir trees. Higher still, thousands of bushy saplings dotted what before had been open alpine meadows. The late-lingering snows, frequent summer frosts and wet soils that used to keep the forest at bay can no longer be relied upon, in a time of rapid climate change.

Those high meadows, I soon realized, are filling with trees almost everywhere. A defining element of Banff National Park’s unique mountain aesthetic—and a vital habitat for many kinds of wildlife—is shrinking as forests expand upslope. While these high-elevation meadows can be expected to migrate further uphill, they need soil, and soil develops very slowly on high mountainsides. Meantime, the meadows are increasingly squeezed between advancing forests below and rocky, soil-less ridges. A warming climate is quietly erasing Banff’s timberline flower meadows.

Snow Creek summit also awakened me to another change I might have missed if I hadn’t let so much time lapse between visits.

Many of Banff National Park’s higher valleys have a sort of male-pattern baldness. The sides of the valleys are forested, but the valley floors are open. The valley bottoms are unfriendly to trees because of their high soil moisture and frequent frosts from the cold air that pools there at night. Streams in these valleys meander through mosaics of grassland, dwarf birch tangles and willow thickets.

Columbian ground squirrels live in the grassy areas and are an important food source for predators such as golden eagles and coyotes. Brewer’s and white-crowned sparrows thrive in the patchy habitats. Moose, elk, grizzly bears and, until recently, caribou rely on the lush meadow forage.

Upper Snow Creek had those sorts of meadows a third of a century ago. Today, however, the grassy parts are hard to find. The dwarf birch and willows are taller, and have filled in most of the open spaces. Charred stems show where park fire crews have tried to burn the shrubbery back, but to no avail.

Researchers recently learned that increased carbon dioxide levels in the air give some woody shrubs a growth advantage over grasses and forbs. If that’s what is happening along Snow Creek and the other subalpine stream meadows in Banff National Park, or even if the causes are as simple as warming soils or changing snowpacks, then it would represent another loss of ecological diversity traceable back to pervasive atmospheric changes.

These sorts of changes may have contributed to the disappearance of Banff’s woodland caribou. Never abundant after Alberta built forestry roads that fragmented their habitat outside the park and improved access for poachers, the Banff part of the herd dropped from 20 or so in the latter part of the 20th century to only five in 2009. All five died that winter in an avalanche. Biologists, however, suspect that wolf predation may have brought their numbers so critically low in the first place.

Caribou avoid predators by staying in remote areas where the snow is deep. Frequent hard winters used to kill off deer and force elk to migrate to low-elevation winter ranges east of the caribou. Today’s gentle winters enable more deer and elk to survive, in turn supporting higher numbers of wolves than would have been normal in the past. That need not be a problem for caribou, which winter in high valleys whose deep snow used to discourage wolves. The increased frequency of mild winters, unfortunately, means that wolves can now travel much more widely thanks to a shallower, denser snow pack. Even before that final accident, climate change had probably already doomed Banff’s caribou.

On my original 1976 hike I had hoped to see a caribou. This time I knew I wouldn’t.

Perhaps most troubling, however, was the stillness. Mountain songbirds are at their most vocal in late June. But day after day I hiked through a sodden stillness broken only occasionally by the song of a kinglet, Brewer’s sparrow, hermit thrush or robin. Olive-sided flycatchers were common in the recently burned forests, but some species were completely missing. The barn swallows that once nested under the eaves of every patrol cabin were gone. The businesslike chant of MacGillivray’s warbler was nowhere to be heard.

I contacted Geoff Holroyd at the CWS when I got back. He confirmed that counts of many migratory songbird species are down across most of the continent. Even in protected places such as Banff National Park their numbers have declined, but it’s because of things happening elsewhere. Many die during their night-time migrations when they get trapped in the lights with which cities, casinos and airports fill the skies. Many thousands are killed by pet cats or collisions with windows. Others can no longer find resting or feeding spots now eliminated by urban sprawl, agricultural intensification or development. Pollutants affect their health and reproductive success. Climate changes add to the stress of migration by exposing birds to unexpected weather and altered habitats.

For all the continuing improvements in Parks Canada’s ecosystem management, Banff National Park’s timberline meadows are shrinking, its subalpine grasslands are being overwhelmed with woody shrubs and the changing landscape is going increasingly silent. And nobody seems to be noticing.

That the causes lie almost entirely outside the park doesn’t get Parks Canada off the hook. Canada’s national parks are dedicated to the people of Canada for their benefit, enjoyment and education, subject to the requirement to keep them unimpaired for future generations.

The enjoyment part is no problem; millions of Canadians go home happy from the parks each year. But the education part requires that they also go home with new insights or understanding about how ecosystems work and how their daily choices affect the earth’s atmosphere and ecosystems – for better or worse. Without that, it’s unclear how Canada, or Canadians, get lasting benefits from those visits. Nor, for that matter, how the parks themselves can benefit—since the global forces threatening to impair those parks are the cumulative effect of decisions made by those same visitors, and their neighbours, at home.

It’s at home, not during our brief visits to national parks, that we Canadians leave lights on in high-rise buildings, putting more carbon dioxide into the air from the wasted energy while dooming migrating songbirds to death by exhaustion in urban light traps. It’s at home where we choose whether to buy gas-guzzlers or fuel-efficient cars. It’s between park visits when we decide between rapid and reckless development of tar sands or more frugal approaches to the exploitation of our boreal forests and the petroleum beneath them. Our most important decisions as consumers, and as voting citizens, are made during day-to-day life.

National parks exist at the will of Canadians—they give expression to our collective sense that nature matters, that our heritage gives us meaning, that some places are so special that they should be passed on like family heirlooms to those who come after us. But they also exist at the mercy of Canadians.

During my 35 years working in western Canada’s national parks, the number of visitors to those parks more than doubled. Some environmental groups argue that’s a bad thing; some tourism groups think it’s great. It could be either. It all depends on what new insights, understanding and motivations those visitors take home with them. Parks Canada’s core mandate says that visitors are to be educated. And if parks are threatened with impairment, then Parks Canada is mandated to avert it. Those two responsibilities are flip sides of the same coin, because the only hope for wise decisions about land use, energy consumption and climate policy is an educated, ecologically literate Canadian population.

.

It is Canada Day, 2011, when I finally arrive at the Trans-Canada Highway near Lake Louise. Countless people are streaming through the scenery, many on their way to or from celebrations of this place we call Canada—a place whose nature we honour and purport to protect in places called national parks. None, I suspect, are aware of the silence in the woods, the shrinking meadows, the missing caribou. Most will go home feeling good about their national park. Far too few, I fear, will go home transformed or enlightened about the nature of their Canada, its ecosystems, its climate—and their choices as citizens.

It appears that, for the most part, Parks Canada got ecosystem management right by the end of its first century. The critical next challenge is ecological literacy. Our parks won’t last their next century without it. We might not either.