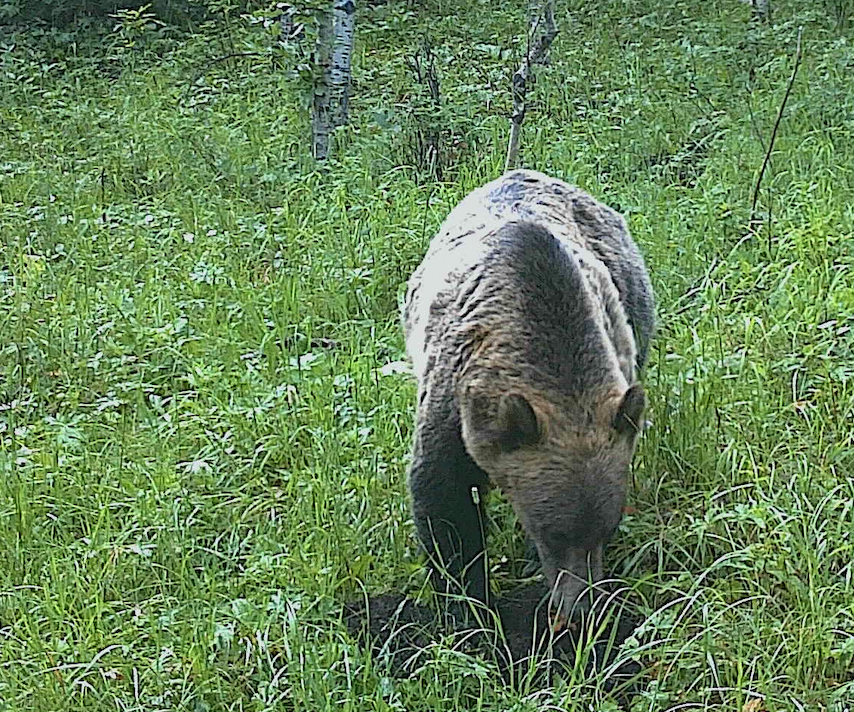

One rainy morning in the Front Ranges of Banff National Park, having just waded the icy-cold Panther River, I rounded a bend in the trail, and there was a grizzly bear. The slope had been burned a few years previously, and the bear was rooting in the lush greenery among the black snags.

I had no intention of turning back, but neither did I feel it would be respectful or wise to try to pass so close to the oblivious bear. After a bit of thought, I pulled out the black plastic garbage bag that was protecting the top of my backpack and tied it to the end of one of my hiking poles. Then I waited until the grizzly finally turned in my direction and spotted me. I waved the garbage bag over my head; the bear flipped ends and took off at a trot up the trail.

Fifty metres on, it half-turned and raised up on its hind legs, then leaned forward in a rabbit-like pose, and projectile-pooped a gusher of green into the woods. Having jettisoned its ballast, the bear dropped to all fours and bolted away up the mountainside. I didn’t bother examining the deposit as I walked past, but the odour was a fecund mix of decomposed greenery and grizzly bear digestive system.

A normal odour for that country. Bears eat a lot of vegetation — young grass and horsetail shoots, dandelion flowers, sweet vetch roots, glacier lily and spring beauty bulbs, and the berries of saskatoon, huckleberry and strawberries. Their digestive systems aren’t suited for breaking down cellulose and other stringy bits, so a lot of what goes down the hatch comes out the other end relatively unchanged. The good bits — sugars, proteins, easily-digested chemicals — remain behind. One reason bears are so food-obsessed is because they eat a lot to get relatively little. Deer, elk, bighorn sheep and bison digest a lot more of what they eat because of their ruminant stomachs — fermentation vats where bacteria and other simple organisms help to turn the unpalatable bits into digestible material.

In order to let their rumen stomachs get that job done, ungulates have to spend a lot of time just lying around, chewing their cuds. Bears, on the other hand, need to keep travelling around to get the nutrition they need. They eat, they excrete, they eat some more.

Hiking the Wishbone Trail in Waterton Lakes National Park one day, Gail pointed out a tiny forest in the middle of trail. The blob of newly-sprouted seedlings, like a flattened chia-pet, was bear poop. The autumn previously, having filled itself up with chokecherry and saskatoon fruit, a bear had paused in the middle of the trail to deposit the remains and make room for more. The resulting pile, after spending the winter under the snowpack, had sprouted dozens of baby shrubs from seeds the bear had failed to digest.

A BC researcher, Aza Fynley Kuijt, tracked 74 grizzly bears and conducted germination experiments on wild huckleberries.1 She found that berries need bears as much as bears need berries. “Bears don’t just eat huckleberries—they help them grow in new places,” she said. “Our findings show that this mutual relationship is crucial for both species, especially as climate change shifts suitable habitats for huckleberries.”

Left to themselves, huckleberries usually fail to reproduce. Less than 1 in every 500 seeds in a huckleberry fruit can actually sprout without help, because the seed coats have chemicals that inhibit growth. In the gut of a grizzly, however, digestive juices remove those chemicals. Kuijt’s research team found that at least a third of the huckleberry seeds excreted by bears subsequently sprout. And since bears travel a lot, those berries often sprout in new places — half the seeds excreted by bears were more than a kilometre from the bushes that produced them, and some got deposited as much as 7 km away.

Bears and berries live in dynamic landscapes. Trees invade meadows and gradually shade out berry patches, enabling other more shade-tolerant plant species to take over. On the other hand, fires and avalanches sometimes kill forest stands, creating new openings of the sort in which berry bushes thrive. Bears, in exploring their home ranges, help bushes like huckleberry, saskatoon and chokecherry find and colonize those places. In turn, the vigorous new berry stands help bears build up their fat reserves each summer and fall, helping them survive through the winter hibernation period. Berries and bears would both be less abundant if they didn’t have one another.

As a student of ecology in the late 1970s, I was taught about symbiosis, a process by which two species come to rely on one another. Symbiosis was considered a bit of an anomaly in a world of inter-species competition. The belief that nature is usually red in tooth and claw — with relationships among plants and animals defined by competition, not cooperation — flowed naturally from the dominant paradigm of the culture in which I was raised, one based on competitive capitalism and a cutthroat market economy that yields winners and losers.

Cooperation between species was so….socialist. And surely that couldn’t be natural.

A half century later, the competitive paradigm has been turned on its head. Symbiosis is no longer seen as an unusual phenomenon — it is the very nature of life and place. Nothing exists in isolation. We are all in this together. Competition among organisms may help drive change and evolution, but the mutually-sustaining relationships among organisms are what keeps everything working. Things don’t exist in opposition to one another; they exist in communion with one another.

The relationship between grizzly bears and berry bushes wasn’t considered to be an example of symbiosis back in my student days, because it was assumed that the benefits only flowed one way: from berry to bear. In reality, as Fynley Kuijt wrote, “Considering the ecosystem services bears provide to the germination and dispersal of shrubs such as huckleberry, the mutualistic relationship between bears and huckleberry should be recognized as an important ecosystem function.”

It should be considered more than that. It should be considered a defining element of what it means to be a real bear, and of what it means to be a real huckleberry. An individual does not exist in isolation from its relationships; it exists as a consequence of them. Without the huckleberry, grizzly bears would still be bears, but they would be less complete ones. Without bears, huckleberries would still be bushes, but incomplete. And neither would live where they do today, and in the ways they do today. They help make each other who they are.

One summer Gail and I took our children on a road trip down the Rocky Mountain chain to the southern edge of Colorado, a journey that took us through the San Juan Mountains. This was where Colorado’s last known grizzly bear died in 1979. The old female bear attacked a hunting guide in self-defence after having been surprised at close range. Against all odds, he managed to kill her by pushing a hunting arrow into her throat as she mauled him.

That incident happened in the southern edge of the San Juans, but as we drove through those mountains it seemed to me it could have happened anywhere there. The San Juans are some of the finest-looking grizzly bear habitat I’ve ever seen: long, steep green avalanche meadows, rich riparian mosaics along tumbling trout streams, aspen forests and dark timber. Grizzly bears simply belong there. But for almost half a century, they have been gone. There are still plenty of black bears to gorge on saskatoons, huckleberries and other wild fruit crops there, and to deposit the undigested seeds in new settings, but the once-abundant grizzly bears are gone. A relationship that once defined both the grizzly and the San Juans has been ended.

Those mountains had a forlorn beauty about them. Like faded paintings, they were less than they should have been. There was a smallness that hadn’t always been there; like an empty chair at the family table, when someone won’t be coming home again.

Grizzly bears have many relationships that make them who they are, and that help make other things who they are too. A few months after that Colorado visit, I rode up Yarrow Creek with other park wardens, heading for a trail that follows the Waterton Lakes National Park boundary west from the head of the valley. For well more than a kilometre, the floodplain meadows looked as if they had been rototilled by some wilderness gardener.

Indeed they had; the churned up meadows were the work of grizzly bears. Constantly rearranged by spring floods, mountain streams tend to meander along their valley bottoms, every so often changing course and leaving their former channels to fill gradually with vegetation. Some of the colonizing plants are valuable bear foods. Sweet vetch is a particular favourite in early spring and late fall, when the stringy roots are full of stored starches and proteins. Glacier lilies and their bright little companions, spring beauty, similarly store nutrients in underground structures – bulbs and corms. Grizzly bears follow their noses through the meadows and use their powerful forelegs and long claws to tear up sods and eat the hidden treasures.

But just as is the case with berry bushes, those bears are not exploiting that food source; they are sustaining a relationship. Sweet vetch and other floodplain plants are pioneers. They thrive best on recently disturbed ground where there is little competition from other plants. As the meadows mature, those other plants take over and the pioneers gradually become scarce. When a grizzly bear digs its way through a meadow, however, it sets the successional clock back by creating anew the raw, fresh soil in which those plants thrive. At the same time, it leaves fragments of roots and bulb in the newly cultivated soil. When human gardeners do that, it’s called dividing perennials. When bears do it, it’s the same thing. Bears are gardeners too.

Sweet vetch would still exist if there were no grizzly bears. It still grows in the San Juans, after all. But its distribution and abundance are different there than when its relationship with the grizzly bear was still intact. Along Alberta’s Rocky Mountain front ranges, whole slopes of yellow and purple sweet vetch offer mute evidence that the great bear still lives here; they would be limited only to soils renewed by other kinds of disturbance if it didn’t. Like in Colorado.

Popular hiking trails like Chester Lake, in Alberta’s Kananaskis Country, are closed annually to allow grizzlies to forage in peace in glacier lily meadows that would have become grass and willow long ago if it weren’t for the annual renewal of a relationship that benefits both the flowers and the bears — and hikers, who thrill to the sight of the bear diggings, watch the forest edges warily, and take pleasure in the delicate, golden beauty of the lilies.

Those relationships do more than benefit the plants, the bears and the hikers. They define them. Each is, in part, the other because each helps make the others whole. Flowers, bears… hikers too.

Hikers in the San Juans don’t see roto-tilled meadows any more. They don’t worry about surprising a grizzly bear. “It must be poor life that achieves freedom from fear,” wrote legendary conservationist Aldo Leopold back in the 1940s. Grizzlies still occupied the San Juans then, but Colorado was well on the way to achieving the poor life of which Leopold warned. Colorado’s mountains today remain no less beautiful, but there is a hollowness there that makes them less than they were, and that makes those who sojourn there a little less whole too.

The bear makes the huckleberry more of what it was meant to be. The huckleberry makes the bear more of what it was meant to be. And both, I would argue, make us more of what we were meant to be. Our relationships, after all, are who we are.

One August morning Gail and I hiked in to a sunny mountainside in southwestern Alberta to pick our winter supply of huckleberries. It was a bumper year; the bushes were heavy with fruit. We were soon lost in the task, hunkered down a few metres apart, surrounded by the peace and beauty of the place. Birds rustled in the bushes around us, filling up with fruit that would help to power their fall migration flights. Huckleberries have many relations; some have feathers.

A particularly loud rustle made us look up. Maybe ten metres away, a grizzly bear had just stepped around a spruce tree and discovered that this berry patch was already taken. We were all taken aback, especially Gail who was closer to the bear than me and had also left her bear spray by her pack. But the grizzly evidently had the same understanding of berry-picking etiquette as we did, and it turned and retreated into cover, leaving the patch to us. Not entirely fair, as there is a good chance that one of its ancestors had relieved itself there and helped get those berries growing, but the whole mountainside was covered with fruit, so there was plenty to go around. The bear huffed its way past us a few minutes later and was soon comfortably ensconced in his own patch, farther up the slope.

The mountains paid no attention to the encounter. They have their own relationships with the world and they live in far deeper time than the rest of us. To the mountains, we were probably all one thing; part of its coat, as it were. The berries, the bear, the humans — I suspect those mountains saw us all as one. In ways that matter to the workings of this world, we are. And we’re all the better for it.

- Kuijt AF, Burton C, Lamb CT (2024). Effects of bear endozoochory on germination and dispersal of huckleberry in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. PLoS ONE 19(11): e0311809. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0311809 ↩︎

You see so much more than most of us, and then share it with us through the gift of your writing.

LikeLike